Neglected Nordics

Modern Magazine, July 2018

NAMES SUCH AS ALVAR AALTO OF FINLAND, Hans Wegner of Denmark, and Stig Lindberg of Sweden roll off the tongue of even a modestly informed admirer of Scandinavian modernism. True aficionados can readily identify three, four, or as many as five star designers of the mid-twentieth century from each country in the region—except, very likely, for one: Norway.

Published in Modern Magazine in July 2018

NAMES SUCH AS ALVAR AALTO OF FINLAND, Hans Wegner of Denmark, and Stig Lindberg of Sweden roll off the tongue of even a modestly informed admirer of Scandinavian modernism. True aficionados can readily identify three, four, or as many as five star designers of the mid-twentieth century from each country in the region—except, very likely, for one: Norway.

robo 150 bench and cabinet designed by Torbjørn Afdal and made by Mellemstrands Trevareindstri for Bruksbo, c. 1962, of teak, rosewood, and enameled steel. Courtesy of Wright.

Though their country has a long tradition of craftsmanship, for numerous reasons mid-century Norwegian designers never gained the same international renown as their peers in neighboring nations. Modernism came somewhat late to Norway. The country did not win full independence from Sweden until 1905, and designers seeking to project a new sense of national identity in their work turned to their Viking ancestors for inspiration, creating pieces heavy in ornamental motifs such as knots and dragons.

Modernist influences eventually crept in, but a university-level school of design did not open in Norway until 1939. Shortly after, the nation was invaded by Nazi Germany and endured a brutal wartime occupation, during which German forces destroyed much of the nation’s infrastructure. Tasked with refurnishing Norway’s households, designers in the postwar period focused on simple, well-made pieces of homegrown woods such as walnut and pine (in contrast to the Danes’ use of imported hardwoods such as teak). Design historian Judith Gura (whose profile of sculptor-designer Albert Paley appears on page 90) notes in her Sourcebook of Scandinavian Furniture that the “emphasis on quality and practicality rather than on distinctive design may explain Norway’s failure to produce ‘name’ designers.”

Scandia Prince chair designed by Hans Brattrud, 1960, made by Fjordfiesta, in lacquered, laminated American oak. Courtesy of Fjordfiesta.

Finally, as Richard Wright of the eponymous Chicago auction house points out, Norwegians took a “quieter” approach to design, and, sadly, had the same attitude toward marketing. Norway’s industry and government did not pursue the same aggressive promotional strategy as their neighbors, one that would make “Danish modern” a staple of the interior design lexicon in the 1950s and 1960s.

So let’s redress that inattention. Here are several key mid-century Norwegian design talents whose names you should know:

The one Norwegian designer whose work did gain some traction internationally was Hans Brattrud, whose Scandia chairs have a striking—and often imitated— profile: an array of curved, vertically oriented laminated wood slats set atop a wire frame. First introduced in 1960, Scandia chairs have been manufactured since 2010 by the cutely named Norwegian firm Fjordfiesta.

Had he not died painfully young in 1968 at the age of forty-four, Fredrik A. Kayser might have become an icon of modern design. His furniture has the same dynamic visual appeal as that of Vladimir Kagan. Kayser was one of the few Norwegians to employ tropical hardwoods such as rosewood, pairing them with humbler artisanal materials like cane. One archetypal Kayser design is the Kryss lounge chair, which combines a leather panel back stitched into a rakish X-shaped teak frame.

At the other end of the aesthetic spectrum lies the work of Torbjørn Afdal, which has the spare geometry of furniture produced by Bauhaus designers. A classic example of his work is the Krobo 150 bench: offering a spot to sit and remove your boots when coming home, it’s a sliver of rosewood set on trestle-shaped legs, equipped (as a practical addition) with a pair of drawers for gloves and scarves and such.

Trained in industrial design at the Royal College of Art in London in the 1950s, Sven Ivar Dysthe produced furniture with solid and elegant minimalist lines. He worked in luxury materials such as rosewood, but also created the affordable plywood Laminette chair, a 1965 design that is touted as the all-time bestselling seating piece in Norway. Dysthe also had a playful side, as evidenced by his stackable Popcorn chair of 1968: a padded plastic shell on a metal frame that resembles a skier headed downhill.

Kryss (Cross) lounge chair designed by Fredrik A. Kayser and made by Gustav Bahus, 1955, of teak, leather, and upholstery. Courtesy of Wright.

Though overshadowed by its counterparts in Sweden and Finland, Norway developed a thriving glassware industry in the twentieth century. The star of the field in the postwar years was Willy Johansson, a winner of multiple awards at the Milan Triennale. Known for his brilliant, offbeat sense of color, Johansson is represented in several prominent international art glass collections, most notably that of the Corning Museum of Glass.

Danes are generally disdainful of designers from other nations, but even they bow their heads to Grete Prytz Kittelsen. Peter Kjelgaard, of Copenhagen’s Bruun Rasmussen Auctioneers, calls her work “poetic,” and adds that she and her husband, architect Arne Korsmo, “were like the Norwegian Ray and Charles Eames.” Prytz Kittelsen’s specialty was enamels. An egalitarian designer, she produced both affordable work such as the colorful kitchen and tableware sets made by the manufacturer Cathrineholm as well as lavish enameled silver and gold jewelry. She also collaborated with the Venetian glassmaker Paolo Venini on a striking group of necklaces.

Stripes bowl designed by Grete Prytz Kittelsen, c. 1950–1960, as part of the Stripes collection

made in collaboration with Cathrineholm enamel works. Courtesy of Cathrineholm of Norway

Those who appreciate a rational—as opposed to intuitive—approach to design will be interested in the work of Edvin Helseth, who, unusually, began his career as an interior decorator. He specialized in furnishings systems made of pine components that could be shipped in flat packs, and easily assembled in multiple configurations. As much as it evinces a straightforward theory-put-in-practice sensibility, a design like Helseth’s Trybo adjustable lounge chair of 1965 has an attractively spare grace. His work “was for simple homes and simple cabins,” says an admirer, Oslo architect Richard Øiestad. “It’s one of the reasons he’s forgotten.”

As with that of other Norwegian designers of earlier decades, it is past time to remember his work.

Freedom of Weeds

Feature: Landscape Architecture Magazine in July 2018

When Lise Duclaux arrived for a residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program in Brooklyn, New York, it was a particularly harsh winter. Neverthe- less, the artist frequently walked the streets of the industrial neighborhood bordering Newtown Creek, a designated Superfund site.

Landscape Architecture Magazine, July 2018

WHEN LISE DUCLAUX ARRIVED for a residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program in Brooklyn, New York, it was a particularly harsh winter. Neverthe- less, the artist frequently walked the streets of the industrial neighborhood bordering Newtown Creek, a designated Superfund site.

Duclaux photographed weeds along her walks, then would go back to her studio and execute detailed drawings of the captured images, includ- ing trash that wove its way into the composition. She researched the form of the roots beneath the concrete and then used Copic ink and Posca paint to record it all. She would often send the images to Uli Lorimer, the curator of the Native Flora Garden at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

To Duclaux, weeds are not unlike her, a visi- tor from a foreign land. Though the Belgium- based artist had no intention of overstaying her residency, which ended in June, she found the scrappy plants representative of an age-old de- bate that America returns to now and again: the foreigner who is at one point welcomed, but later considered a threat.

“It’s really fashionable to do the native garden right now, which is a little bit strange for me, especially in New York,” she says. “We accept that people mix together, but we don’t accept that plants can mix and change. For me these [drawings] are im- ages of tolerance, of acceptance, and of diversity.”

She calls the weeds “spontaneous,” “autonomous,” and “cosmopolitan.” She notes, though, that few weeds can be found amid the canyons of Manhat- tan during the winter.

She says that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the first laws written to forbid invasive plants also happened to coincide with laws that limited immigrants from entering the country.

“I want to work with plants that are not behind the fences, like they are in jail, where humans decide where they want the plants, which can stay, and which must go,” she says.

Weeds decide for themselves where they will grow, like homesteaders settling in undesirable areas, or hardscrabble New Yorkers making do.

“We all the time speak about freedom, freedom of speech, and then the plants can’t have the freedom?” she asks. “We know that it’s a weed, and we decide that it’s not pretty. In a way, nobody looks at these as wild plants. But who decides what is pretty?”

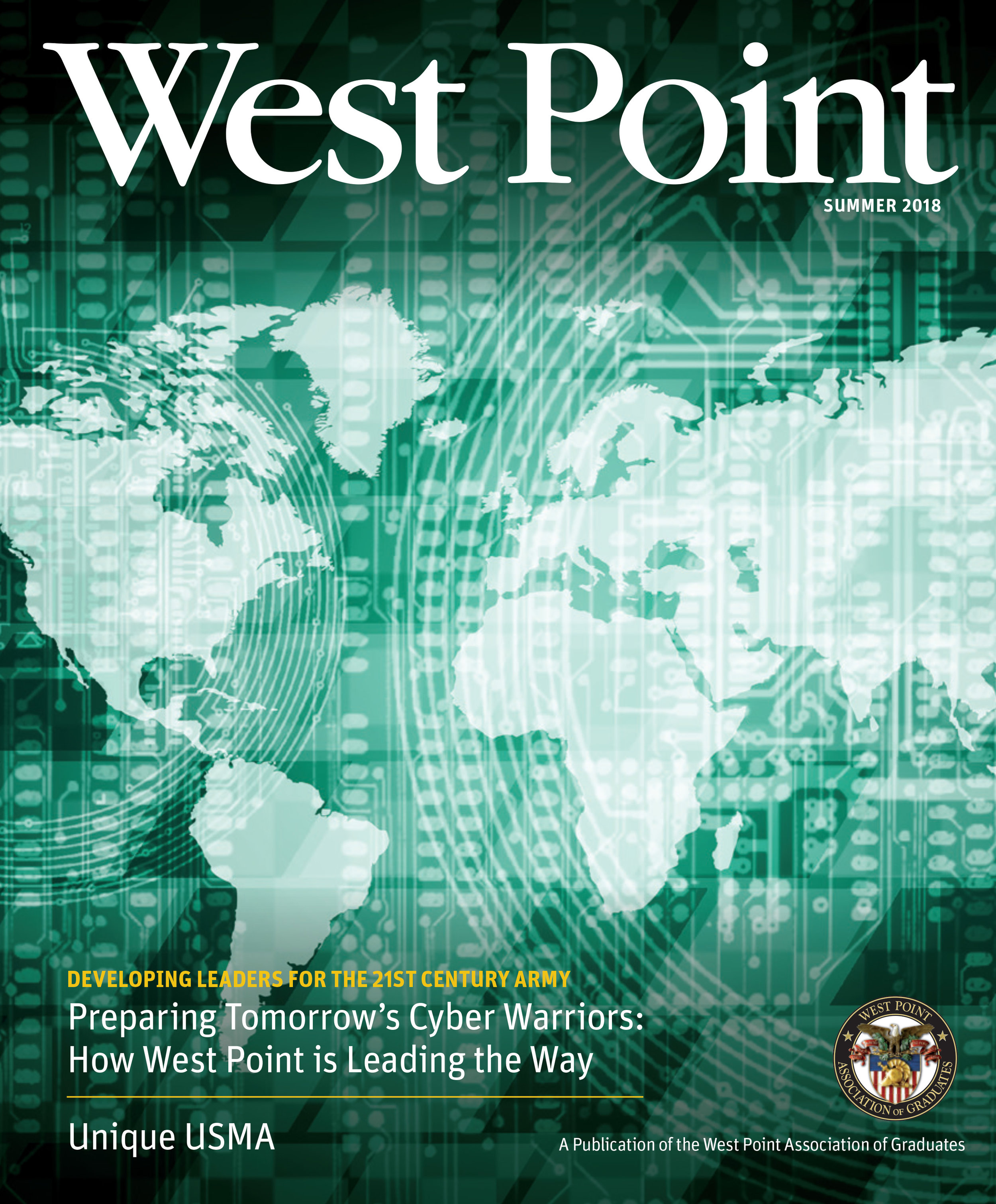

Preparing Tomorrow's Cyber Warriors

Cover story for West Point alumni magazine, Summer 2018

In remarks at the 2016 AUSA Convention in Washington DC, General Mark A. Milley, Chief of Staff of the Army, outlined the challenging 21st Century strategic environment, where future wars will be fought “on a non-continuous, non-linear battlefield, with little higher command supervision and maximum decentralization.” Crises will unfold rapidly, decision cycles will compress, and response times will narrow. A vital part of the U.S. Army’s readiness in such an environment is its capabilities in cyber defense.

Cover story: West Point Magazine, Summer 2018

In remarks at the 2016 AUSA Convention in Washington DC, General Mark A. Milley, Chief of Staff of the Army, outlined the challenging 21st Century strategic environment, where future wars will be fought “on a non-continuous, non-linear battlefield, with little higher command supervision and maximum decentralization.” Crises will unfold rapidly, decision cycles will compress, and response times will narrow. A vital part of the U.S. Army’s readiness in such an environment is its capabilities in cyber defense.

Organized defense of the Cyber domain, with the establishment of both U.S. Cyber Command and Army Cyber Command in 2010, is a relatively recent addition to the Army’s capabilities. Yet, despite the rapidly evolving pace of cybersecurity’s “history,” West Point graduates, instructors and cadets have been at the forefront of the field from the very beginning, providing innovative responses and expert analyses unrivalled by any other institution in the country.

Role of the Military in Cyber Defense

If you can make $500,000 as a senior hacker at the Bank of New York or $50,000 in the Army as a cyber warrior which job do you take and why?

This not-too-hypothetical question was posed by General Keith Alexander ’74 (Retired), former Director of the National Security Agency (NSA) and former Commander, United States Cyber Command.

“The military loses out on that in almost every case—but with the military you can get an education, training, and you get to do stuff in government that you can’t do in commercial life: conduct offensive operations to support national security requirements legally in cyberspace,” he said.

With significantly higher pay offered by private sector for cyber expertise, what draws cadets at West Point to study cyber beyond the opportunity to legally hack? Probably the same reasons that have attracted cadets to West Pont for more than two centuries.

“It fundamentally comes down to service, and ‘Do you want to serve your country?’” said Cadet Lexie Johnson ’18, a member of the West Point Cyber Policy Team, one of two USMA Dean’s Teams that compete in the cyber realm. “I think that’s where you’re going to find distinctions: You’re either doing this job for money or you’re doing it for a greater purpose.”

Major Sang Yim, a cyber instructor in West Point’s Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science (EECS) and Officer in Charge of the Special Interest Group for Security, Audit and Control (SIGSAC), a cadet cyber club, said that he finds that camaraderie draws talent to West Point rather than the private sector.

“You’re all on the same team working on the same goal to defend the country,” he said. “In business, you have to beat out the guy next to you, and you’re not going to have that team aspect.”

History Being Made Now

Few would have predicted even 10 years ago that cybersecurity for the nation would become as omnipresent in the public awareness as it is now. But Alexander said that as far back as the late 1990s “we saw people messing around” with a series of cyber attacks by Russians on the U.S. government.

“There was a series of three or four [U.S.] operations to identify the source of the attacks that gave us concern,” he said. “Back then it was more of a niche operation by the NSA to identify the attacks than a broad scale response.”

By 2005, the “niche” NSA operation had significantly grown, and NSA was developing their next generation collection platform, called Trailblazer. The contract on that platform was terminated three days before Alexander took over NSA. Then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld charged Alexander to come up with a new platform that would shift defenses from analog to digital. Shortly thereafter came the large-scale 2007 cyber attacks on the Estonian government and banking system amidst tensions with Russia. And then came a 2008 cyber breach predominantly in United States Central Command, spread by thumb drives. This breach eventually led to the creation of U.S. Cyber Command, which became operational under Alexander in 2010.

The 2008 attack marked the beginning of a new kind of threat in warfare: it wasn’t someone simply stealing information, it was someone exploiting and corrupting the U.S. military network with a virus. “We identified the attack on 24 October 2008 and by the next day we had a solution on the network,” said Alexander. “It was then that Secretary [of Defense]Gates decided to bring together the offense and the defense that would become Cyber Command.”

Alexander pulled together a team that included now-General Paul Nakasone, now Rear Admiral T.J. White, now-Colonel Suzanne Nielsen ’90, presently Professor and Head of the Department of Social Sciences at West Point, and Jen Easterly ’90, currently Managing Director at Morgan Stanley and Global Head of the Cybersecurity Fusion Center. Together, they developed the intelligence framework for U.S. Cyber Command and presented the concept to then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates. “To say they were met with strong resistance would be an understatement. We knew we would need this in 2018, but that wasn’t as apparent in 2008,” observed Brigadier General Jennifer Buckner ’90, who joined the team in 2010.

But U.S. Cyber Command was approved, as was Army Cyber Command, which evolved to include the establishment of the U.S. Army Cyber School at Fort Gordon’s Cyber Center of Excellence. Buckner, the first Cyber School Commandant, helped design the curriculum, and drew upon her West Point education, emphasizing engineering and technology. “We’re teaching them to solve hard problems not by telling them what to do, but by teaching them how to think,” she said.

Laying the Foundations for a Cyber Team

Alexander said he learned Fortran computer coding while he was a cadet at West Point. But while those hands-on programming skills have served him well, he stressed that the team-building skills he learned at the Academy is what helped him to grow as a leader in the cyber realm. “West Point teaches you to figure out what you don’t know, and how to get the right people to work with you,” he said.

Many of the people that Alexander surrounded himself with during the early days of cyber defense would go on to build and lead some of the Army’s and West Point’s key institutions in cybersecurity. Buckner was there when he set up U.S. Cyber Command, and she served as the U.S. Army War College Cyber Fellow at the NSA. She was recently promoted from Deputy Commander, Joint Task Force-Ares to Director of Cyber, G-3/5/7, U.S. Army. She said the field is experiencing tremendous growth. The Army Cyber School graduated its first class in 2016, and, where just three years ago there were only 18 students, today there are nearly 800.

“Education is so important. Our future leaders are the lieutenants and captains, our junior ranks, so developing that talent is important,” Buckner said, adding that she continues to call on the talents at West Point to work on some of the Army’s toughest cyber problems.

The U.S. Army Cyber Branch, established in 2014, first welcomed 15 graduating second lieutenants from the USMA Class of 2015, and saw 20 cadets from the Class of 2018 branch Cyber. At the Academy, cyber education continues to grow and become more interdisciplinary (see “Developing the Cyber Warrior,” sidebar on page 11). All plebes are required to take IT 105 Introduction to Information Technology, a core course introducing cyber concepts, and then may choose to pursue an interest in the field with advanced level courses, clubs or participation in a competitive cyber team. Courses that were once limited to Computer Science, IT or Electrical Engineering majors now welcome economists and foreign language and English majors.

“For the English major in any other school it may not be as critical, but considering our graduates are going to be lieutenants and they’re going to be in the Army using our information systems, we want them to understand cyberspace, because our weakest link right now is the user,” said Lieutenant Colonel W. Clay Moody, Ph.D., Assistant Professor in EECS and a coach for the award-winning Cadet Cyber Competitive Team (C3T).

For cadets who aren’t sure whether cyber is for them, there is a chance to get their feet wet at SIGSAC. The club’s casual atmosphere delves into security issues in many spheres, not just cyber. (They’ve even held lock picking contests.) But the primary focus is on cyber and hacking. The group meets every Monday and is a mix of men and women, some of whom are technically proficient and some who are not.

“There will be people who will be interested in the tech side but don’t get too involved because they’re spending their time in policy,” said Cadet Preston Pritchard ’18, the Cadet in Charge of the group.

Pritchard said that the club is also a good place for students from a variety of backgrounds to begin to meet on the common ground that is cybersecurity. But the two groups that continually overlap are the tech-savvy students and the policy-savvy students. “They’re two very different groups, but they are both equally important,” said Pritchard. “The tech side can’t operate without knowing the law and the policy side can’t operate if they don’t know a bit about tech.”

After competing amongst themselves, the students’ talents begin to emerge. “From there we pick people who are good at what they do,” said Pritchard. “Those people who are good at tech we encourage to try out for the C3T.”

Next year, Moody said, the C3T team will operate as three sub- teams that reflect the real world of cybersecurity: one team will focus on cyber defense, another team will focus on offense, and the third will be a more “full-spectrum” Capture-the-Flag team. In Capture- the-Flag competitions, cadets are authorized to compete on a cyber range, where they can safely engage in hacking and defending. A hacker may be searching for a hidden message that requires them to exploit a vulnerability in the system in order to recover that message, which could be a string of characters representative of a social security number or war plans. Most of the competitions run about 48 hours and occur online. “It’s about understanding the foundations and be willing to dive in and work on it,” said Moody. “To be successful on the teams, you need to be inquisitive.”

Although many competitions take place online, members of the C3T and Cyber Policy Dean’s Competitive Teams were able to travel to the inaugural NSA Cyber Exercise (NCX) for the U.S. Service Academies at Annapolis this year. Cyber policy team members, SIGSAC members, and cadets in cyber-related classes accompanied C3T to the event. After 17 years of the NSA Cyber Defense Exercise (CDX), a weeklong exercise which featured each academy’s teams defending against NSA attacks from their home location, faculty from the military academies and United States Cyber Command joined the NSA in developing and executing a wholly redesigned competition. The NCX features in person head-to-head attack and defend scenarios, as well as policy and forensics scenarios. The benefit of competing in person is the chance to get to know cyber teams from the other academies.

“It’s great because we know each other and we’ll probably get to know each other in our careers,” said Pritchard. “Cyber is a joint effort. If you go down to Fort Meade or Fort Gordon you have Air Force next to Marines next to Navy, and civilians too.”

Cyber Thought Leadership: The IntellectualHome of the Army

Lieutenant General Rhett A. Hernandez ’76 (Retired), currently serves as the West Point Cyber Chair at the Army Cyber Institute at West Point (ACI), an outward-facing research organization that was established in 2012. He was the first Commanding General of U.S. Army Cyber Command upon its activation in 2010. Hernandez said that West Point addresses cyber education not just through electives in computer science and math, but also through policy, law, ethics, cognitive behavior, and even cyber history.

“We need to think about how to increase thought leadership by not necessarily focusing on today’s problems, but by helping the Army and others think about what could be next,” he said. “And to add to the body of knowledge, we need to develop strong partners in the commercial sector, industry, academia, and government.”

Colonel Andrew Hall ’91, Director of the ACI, said the organization encourages collaboration with academic researchers based at universities around the country, where the tenured faculty model complements West Point’s rotating model for instructors who bring in knowledge directly from the field to the Academy. The university professors’ theoretical rigor builds on the West Point faculty’s on- the-ground experience.

“West Point is the intellectual home of the Army. Thought leadership is what the Institute started out on—no one else in the Army has the intellectual freedom to publish in peer-reviewed journals,” said Hall. “We’re trying to expand the talent pool we work with, and to expand knowledge across the entire cyber community.”

Though the ACI works with many partners outside of the Academy, West Point reaps the benefit of having many of its researchers teaching cadets and coaching competitive cyber teams. “We have ACI faculty who teach in eight of the 13 academic departments, covering courses as diverse as Cyber Ethics, Law, History and Policy to Mathematics and Computer Science,” said Hall. “Diversity of thought is key to working in cyber.”

Building on IT: The Power of Interdisciplinary Teams

For today’s cadets majoring in non-IT disciplines, the attraction to cyber is simply part of being a digital native. Few draw hard lines between their discipline and cyber.

Cadet Nolan Hedglin ’18, who as a firstie was majoring in math and physics, said that he and Johnson were part of the first cohort able to take courses that were once limited to computer science majors. He said voices from different disciplines enrich the cybersecurity field. “We bring another perspective to cyber and that perspective will have long term effects on how the culture will shift,” he said.

Both Hedglin and Johnson were part of the West Point Cyber Policy Team, a Dean’s Team (like C3T) coached by Major Patrick J. Bell ’05, a research scientist with the ACI and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Sciences. The team took home first place in the Atlantic Council Cyber 9/12 Student Challenge in Geneva in April, and won the Indo-Pacific Cyber 9/12 Student Challenge in Sydney, Australia in September 2017.

“Cyber is intellectual pluralism at its best,” said Johnson, who is majoring in international relations and Russian. “The cyber domain demands pluralism, because the repercussions can affect the economy,politics, and infrastructure,” she said. “We need cyber experts in a variety of realms to predict and understand their sectors.”

The Cyber 9/12 Challenge competition scenario involves briefing an important decision maker like the National Security Advisor on a rapidly unfolding situation such as a cyber attack. Competitors are not looking for a technical solution, though technology is certainly a component. The competitors must respond to immediate needs and make recommendations based on imperfect information.

“Cadet Cyber Policy Team members get to wrestle with a lot of the most pressing issues at play,” said Bell. “The speed with which the media will react to an event today is unprecedented; we’re expecting adversaries to prepare their communication responses before they even initiate actions.” Bell said traditional international relations theories are relevant in the cyber domain, though they may not apply as well as they do with warfare scenarios involving nuclear weapons. But the fact that the established theories are an imperfect fit intrigues Bell and his colleagues, and presents an opportunity to develop new ways of thinking. He added that decisions in the cyber domain must blend computer science skills with policy knowledge in order to best deliver effects.

Digital Disruptions

From the very early days of cyber warfare, traditional command structures and the very language of warfare have been challenged to evolve, since the virtual world of cyberspace encompasses and extends beyond land, air, and sea.

“Culture aside, a lot of what delineates the Army from the Air Force and the Navy in cyber is what we consider to be tip of the spear for that mission, and for the Army it’s the soldier, the individual soldier interacting with humans on a daily basis in theater” said Hedglin.

Buckner agreed, adding that in cyber sometimes the junior ranks represent the tip of the spear, as cyber is a domain they grew up in. “One of the ironies is that, in most branches of the Army, you feel ‘established’ in a higher rank, but in this one, we recognize that our lower ranks are the future,” she said.

Hall noted that the typical Army unit operates under a commander, supporting the infantry commander, at the time and place of the commander’s choosing. He said that cyber warriors need to react more quickly and distinctly than their real-world counterparts. “In cyber, the most important thing we’re doing may be preventing attacks way before a kinetic attack,” he said.

Not only is the command structure evolving with cyber warfare, but so is the language required to direct action. Part of the reason West Point’s Cyber Policy Team took first place in Geneva was because they were best able to translate technical rhetoric into something that civilian policy makers could understand and act upon. “This is an emerging domain and an emerging threat that needs to be translated appropriately and effectively,” said Johnson.

Communicating about cyber events can prove further challenging when the effects of an event can seem elusive in the physical world. The damage is not something one can necessarily see. Even the term “warfare” irks some in the field.

“Talking heads have too often used the phrase ‘cyber warfare’ to describe events like the OPM and Equifax hacks. But is it warfare? Not as I understand it,” said Lieutenant Colonel Michael J. Lanham, Ph.D., Director of the West Point Cyber Research Center, whichocuses on cadet and faculty development in cyber and complements the ACI’s outward focus.

Lanham said he sometimes uses “traditional military operations terms on non-traditional terrain” to help shape discussions about cyber warfare. However, equating cyber attacks to historic battles often proves a weak analogy, he said. He noted that most comparisons come from commentators looking for easy analogies, with several warning of an impending “cyber Pearl Harbor.”

“That analogy breaks down,” he said. “The Pearl Harbor attack was the seminal moment that provoked a full entry of the U.S. into World War II and led to the unconditional defeat of the Axis powers; what we’re experiencing is not that. We are experiencing industrial and national espionage, experiments in sabotage, but not crossing the threshold into warfare yet.”

The hyperbole of a “cyber Pearl Harbor” gives the perception we are waiting for a catastrophic event in the physical realm, like a large chunk of the power grid going down. But the U.S. has already experienced several large scale cyber events that have not galvanized the public in the manner of Pearl Harbor or even 9/11.

“I’ve heard a lot of people say it’s the same warfare in a different domain, but in many ways, this is not the same warfare,” said Bell. “In the Cold War, you could not go in and ... get information on 87 million people in the country and then work to try to manipulate them at a granular level without anticipating any retribution.”

Hack Back

Almost everyone interviewed for this article said the military’s ability to “hack back” attackers remains a strong incentive in recruiting potential cyber soldiers away from the more lucrative private sector. Still, the Army follows very strict legal guidelines and authorities that they adhere to during cyber operations. Hacker training is only conducted on cyber ranges and in controlled environments.

“There’s no right to defend your cyber domain like you can defend your house,” notes Moody. “A lot of the hacking skills you may want to use in the private sector are going to come with handcuffs, but in the Army, the things you can do with those same skills are going to win you medals.”

The ability to hack and defend the nation may attract talent to the Academy and the Army, but all the hacker talent in the nation isn’t going to make an impact without cooperation from the private sector. Hernandez says it’s all about partnerships. “There are all kinds of numbers out there, but many say more than 90 percent of the critical infrastructure, from financial to energy to transport, is all owned by the private sector,” said Hernandez. “In order to better defend the nation, you have to have strong public-private partnerships at all levels—and that’s much easier to say, but harder to do.”

Alexander’s primary concern, as has been voiced by leadership in both the intelligence and defense communities, is forming strong public/private partnerships. “We created our government for the common defense and that includes the private sector,” said Alexander. “We don’t question well enough what the role of government is and what the role of the private sector is.”

Alexander said with the proper oversight the government can defend the private sector while addressing privacy concerns. He added that there’s a “perception problem” of what people think the government will do if it gains access to private data. “Think about how many phone calls, texts, emails, and social media posts you see every day, and multiply that by the number of people in this country,” he said. “No one is out there reading all that. We need to encourage people to get the facts: We’re doing this to protect you.”

A Solid, Ethical Career

When Pritchard was growing up in the small farm town of Ixonia, Wisconsin, his family did not have internet service. “I got into computers by not having internet access, so I turned inwards to the computer,” he said. “Instead of spending time browsing the internet I spent time in the windows operating system, breaking it apart and putting it together again.”

When his family did get the internet, he was able to get many of his burning tech questions answered. He said that as an outdoors person he wanted to branch Infantry when he came to the Academy, and then move on to Ranger School, but his interest in cyber continued to pull him in another direction. “Before, it used to be you could do one or the other, but now you can do both,” he said. “I can still do cyber and I get to serve my country.”

Today, his future in cyber looks secure and wide open. He has recently chosen to branch Cyber, where he’ll be able to hack back. But it’s not what people think, he said. It takes hours of training and supervision before anyone gets approval to respond to a cyber attack. Pritchard said sometimes the standards, which are rooted in law, make cyber warriors feel as though “their hands are tied.” But at the same time, the standards reveal what he and his colleagues are fighting for and who we are as a nation.

“In Russia or China, they can recruit off the street and say, ‘Attack this target,’” he said. “They’re able to do that because they are not held to the ethical standards that we hold ourselves to.” His fellow cadets agreed. “This environment is the most conducive in learning how to ethically hack, and then translate that into future jobs you can do,” said Hedglin, adding, “And the mission itself is extremely rewarding.”

Florsheim/Goldberg: an extended conversation

The tale of the mother-in-law/son-in-law relationship isn’t one that’s often told. But the intellectual give-and-take between architect Bertrand Goldberg and artist/collector Lillian Florsheim takes elegant form in an upcoming auction at Wright Auctions in Chicago

Modern Magazine, February 2018

"It’s an unusual story,” said Richard Wright in the New York gallery for his Chicago auction house.

Indeed, the tale of the mother-in-law/son-in-law relationship isn’t one that’s often told. But the intellectual give-and-take between architect Bertrand Goldberg and artist/collector Lillian Florsheim takes elegant form in an upcoming auction at Wright Auctions in Chicago, titled Florsheim/Goldberg: an extended conversation. The auction is set to be held on Thurs., Feb. 15 at 12:00 p.m. (central time).

Model for Health Sciences Center in Stony Brook, NY, by Bertrand Goldberg. Image courtesy of Wright Auctions.

At the New York exhibition preceding the auction there was perhaps the most telling, modest, and intimate of all the pieces for sale: a spice rack that Goldberg designed for Florsheim. Composed of perforated stainless steel and metal engine parts, the kitchen accessory is appropriately valued at $2,000 to $3,000, despite its humble media. The piece reflects what Wright describes as an “intergenerational and familial” relationship where “the influence cut both ways.”

“They shared a lot of conversations about specific shapes of curves,” he said. “And they really did the deep dive into ideas of form and space.”

Spice rack for the house of Lillian Florsheim by Bertrand Goldberg. Image courtesy of Wright Auctions.

Goldberg married Lillian’s daughter Nancy Florsheim in 1946, thus beginning the conversation between the architect and the artist. Their shared interest in what Wright called “the dementiality of three dimensional curves” can be observed in some of the pieces by Florsheim, namely an untitled 1965 sculpture where clear acrylic rods poke through a black Plexiglas square. And while curves occupied a good chunk of their theory thinking, one can imagine color took precedence too, explicitly in works collected by the two, such as Josef Albers’ Dark (1947) from Goldberg’s collection, and Formation de la Matiére (1951) by Georges Vantongerloo—which Florsheim acquired directly from the artist—an exploration of color and form in oil on panel.

“Lillian had a personal relationship with Vantongerloo,” said Wright, who described Vantongerloo as “one of the style artists right up there with Mondrian and company.”

Florsheim already had an impressive art collection evolving well before Goldberg met his wife.

Dark by Josef Albers. Image courtesy of Wright Auctions.

“Later she made choices that were influenced by Bertrand, as he got her to look at and at some of the more challenging more avant-garde European material,” said Wright.

Of course, the auction includes plenty of architectural drawings, posters, studies, photos, and models, such as two models by Goldberg for the Health Sciences Center at SUNY Stony Brook, which can be appreciated as pure sculpture in their simplicity of form.

The collection also veers into other aspects of the family’s history. Nancy Goldberg’s development of a boutique hotel tower designed by her husband required a marquee restaurant. The family convinced Maxim’s de Paris owners to open their first franchise in the Astor Tower Hotel on Chicago’s Gold Coast. Decor from the former restaurant ushers in the more esoteric aspects of the collection, such as art nouveau posters, champagne buckets, and other ephemera that add an eccentric footnote.

While the auction is primarily drawn from modernist collections, there’s also a keen appreciation of ancient Roman glass, an impressive amount of pre-Columbian sculpture, an Indonesian cowbell, and John Cage’s Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel (Plexigram I).

The catalogue’s perforated protective cover is reminiscent of Florsheim’s Plexi piece. It is written by Nancy and Betrand’s son, the architect Geof Goldberg, who respectfully distinguishes two independent thinkers that clearly appreciated each other.

“It’s not for us to say who influenced who,” said Wright. “But they were literally in conversation in a very direct way.”

West Point Names Barracks for B. O. Davis, Jr.

Cover Story: West Point Magazine, Fall 2017

In significant gesture to its African American legacy, West Point dedicates its newest cadet barracks to General Benjamin O. Davis Jr., who overcame great prejudice at the Academy and went on to become commander of the Tuskegee Airmen.

On August 18, the United States Military Academy honored the late Air Force General Benjamin O. Davis Jr., Class of 1936, by naming its newest barracks after the four-star general and commander of the famed Tuskegee Airmen.

“His name, etched here in stone, is a perpetual reminder of his incredible legacy and example that will inspire all future leaders of character that pass through West Point’s gates,” Lieutenant General Robert L. Caslen Jr. ’75, 59th USMA Superintendent, said at the barracks dedication before an audience that included alumni, faculty, cadets, members of Davis’s family, and Tuskegee Airmen who served under his command.

AWest Point committee was formed in 2014 to recommend a name for the barracks and thoughtful deliberations ensued (see “What’s in an Name?” on page 18). The committee considered recommendations from cadets, alumni, and historians. The result was that the Superintendent chose to recommend that the Department of the Army choose Davis as the building’s namesake, selecting him from a field of several worthy nominees.

Major General Fred A. Gorden ’62 (Retired), the 61st Commandant of Cadets (1987-89) and the first African American to hold that position, met Davis on several occasions. Gorden served as Davis’s escort for the 1998 White House ceremony in which Davis was promoted to four-star general by President Bill Clinton. Gorden said that the choice of Davis for the barracks name resonates well beyond the walls of West Point.

“While the scope of his wartime leadership and generalship may not rival that of Grant, Pershing, MacArthur, Eisenhower, or even a more contemporary Schwarzkopf, General Davis’s stature as an American fighting man of indomitable allegiance, courage, and resolute spirit is second to none,” said Gorden.

Caslen later emphasized that one of Davis’s greatest qualities was that he always persevered and stuck with the team, no matter what the challenge, eventually earning the trust necessary to lead.

“If a leader is to be effective and inspire and motivate people to work toward a common goal, then the team has to trust that leader,” he said. “Trust is earned, and is a combination of competence and character. General Davis certainly possessed both—his life and his service attest to that.”

A First Among Equals

Davis was not the first African American to graduate from the Academy; he was the fourth. Before him came Henry O. Flipper, Class of 1877; John Hanks Alexander, Class of 1887; and Charles Young, Class of 1889, the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel. Young mentored Davis’s father, Benjamin O. Davis Sr., who went on to become a brigadier general—the first black general officer in the U.S. Army—in 1940. The senior Davis then groomed his son to succeed at West Point.

Davis also had the support of Chicago Congressman Oscar Stanton De Priest, the NAACP, and the black press. Other black cadets had tried and failed to graduate in the time between Young’s tenure and Davis’s, but they did not have a comparable support system outside the Academy.

This didn’t mean that Davis’s experience at West Point passed without serious tribulations, quite the opposite. In fact, he was “silenced” during his four years at the Academy and endured sustained harassment because he was black. As time passed, however, he never turned his back on the institution or on his duty as a soldier.

“He was not bitter, he was not resentful, and it did not deter him from his ultimate goal,” said his nephew Judge L. Scott Melville. “There’s a saying about goals, ‘Keep your eye on the prize.’ Well Ben’s prize was to graduate from this institution and he did that.”

Herman E. Bulls ’78, Board Member of West Point Association of Graduates (WPAOG), said Davis’s experience was indicative of his times. “He tended to represent so much about our country, including where our country was in the 1930s,” said Bulls. “He was the first black cadet to graduate in 47 years [after Young], and in that time we had Plessy v. Ferguson [the 1896 Supreme Court decision upholding ‘separate but equal’ treatment of blacks] and the Jim Crow era, so you naturally don’t have another graduate until Davis—and not that many afterward. I’m only number 59.”

Dedication Day Amidst Debate

Dedication Day, B.O. Davis Barracks

The new Davis Barracks rises high above post, taking its place within the profile of the iconic West Point skyline, tucked into the landscape below the Cadet Chapel.

On the warm sunny morning of the building’s dedication, most of the participants chose to climb the 71 steps of the steep grand staircase to reach the barracks formation area which skirts the building, providing spectacular views of the Hudson Valley. One after another, they reached the top of the steps to the plaza and marveled at the building’s impressive central tower. Among the guests were a civilian who had named his son for Davis, the highest-ranking woman to graduate from West Point, and a mom who came to see her son officially become a plebe the following day at Acceptance Day (A-Day).

As Lieutenant General Nadja Y. West ’82 stepped onto the apron, she fixed her eyes on the tower. West didn’t notice Captain Sara Schubert ’13 mouth the word “Wow!” at her arrival. As she looked for her seat at the back of the dignitaries’ section, an official informed her that she, the U.S. Army Surgeon General, would be seated in the front row. It was an unconsciously humble gesture, echoing the character of the day’s honoree. Schubert watched the scene play out with appreciation.

“I’m in medical services, so she’s our leader,” Shubert said of her boss, before gesturing to the tower, adding, “I think we’re really setting the example that this is West Point and we’re moving forward.”

West called the journey up the stairs “amazing.”

“I never thought, 35 years ago when I was graduating, that I would ever see a barracks dedicated to such a great African American leader,” she said. “I mean we’ve really come a long way and in this environment that we’re in now, I think it’s also a very timely way to honor a real patriot, a real leader.”

West gave voice to what was on the mind of nearly everyone: the riots in Charlottesville, Virginia had occurred a mere six days before. The crowd was filled with many African American men and women who had graduated from the Academy and had served in the military. Many said that the dedication reassured their faith in the nation. “From the Revolutionary War forward you’ve had African American patriots, not a lot documented in history or through historical monuments, so I think this is just an opportunity to show the contribution and dedication of all of our soldiers,” said West. “I think naming the barracks for Davis shows that diversity makes our nation what it is today.”

Nearby, Patrice Allen took in the scene. Allen, a member of the West Point Parents Club of Western New York, came down from Buffalo to West Point to see her son Terrence (TJ) transition from new cadet to plebe on A-Day the following day, just like his father, Lieutenant Colonel W. Tyrone Allen ’83 (Retired), once did.

“I’m proud of what my family has done for our country, what my husband has done, and what my son is planning to do,” she said. “It warms my heart to see what the leadership is doing here by standing up and publicly acknowledging Davis and the sacrifices that so many other people have made.”

Before being called away by her husband to have their photo taken with West, Allen added that she was also thrilled to see so many African American women participating in the ceremony, especially Simone Askew ’18, the newly appointed First Captain, the first African American woman to hold the post. Moments later, Askew could be seen taking a selfie with General West as Cadet Netteange Monaus ’18 waited to speak on behalf of the Corps of Cadets at the dedication ceremony.

“We’ve really come full circle. Now you’re seeing a barracks in honor of another great man in history, and then seeing the whole community coming together to support it,” said Monaus. “America’s history has had its past and there are still issues, but this shows there’s still a greater community that sees the good in everyone.”

Making of a Monument

West Point is a campus of monuments. It could easily be argued that barracks are the Academy’s most vital monuments, since each day the cadet barracks swirl with the activity of a bustling campus. The significance of the buildings’ names cannot be overstated, nor can the process of how they come into being.

“We have barracks named for MacArthur, Bradley, and Eisenhower,” said Colonel Ty Seidule, Ph.D., Professor and Head of the USMA Department of History. “The barracks represent a pantheon of American military heroes.”

Archie Elam ’76, WPAOG Board Member, said that while Davis may be universally admired, the choice of using his name for the barracks did “reset the relationship with our diverse graduates.”

“But, no one started out with some idea about the barracks with the name of a person of color,” he said. “They voted for General Davis because of his character, not his color.”

In many ways, the process of naming Davis Barracks stands as one of his greatest legacies. During the symposium following the dedication ceremony, Seidule tipped his hat to cadets who had lobbied for the barracks to be named for Davis, which, heemphasized, was done within the Academy’s system. Mary L. Tobin ’03, agreed.

“Cadets are taught if you want to make a change, you’d better make a case for it, bring your facts, and your data, and that’s what those cadets did,” said Tobin. “Plus, the leadership listened to them, and it has not always been that way. They gave the cadets a forum. Even if they decided to turn the cadets down, they allowed their suggestions to be presented.”

As a cadet, now-Second Lieutenant Michael Barlow ’16 initiated the petition to name the new barracks for Davis. Second Lieutenant Terry Lee ’17 was his roommate at the time. Lee said Barlow focused on getting his fellow black cadets on board at a town hall meeting where they launched “Operation Tuskegee,” which set out to gather signatures to support the naming. But not everyone was convinced.

“Some people didn’t feel like they experienced the same discrimination that Davis did; they were satisfied here,” said Lee. “Going from door-to-door came with its own set of problems. Some needed persuading. But those that put down their signature are glad they did.”

Barlow pressed on in consultation with Seidule and Lieutenant Colonel Donald Outing, Ph.D., who was at the time an Academy professor in Mathematics and Director of USMA’s Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Equal Opportunity. Both faculty members mentored the cadet on the finer points of drafting the necessary memos to the administration and on Davis’s history.

“At the time it was very inspiring how Barlow, at 21 years old, was spearheading a project that would impact West Point and the Army,” said Lee. Elam said that resistance is an innate part of working within the system, which he recalled was also “an underground wrestle with our diverse grads and with each other.”

“Change like that is uneven and slow, it’s a reflection of the process anytime you want to change the future against the status quo,” he said. “But with faith, the future always wins.”

Once the name was approved, however, the resistance, such as it was, dissipated, said Seidule. As a historian, he knew that Davis qualified for the honor well beyond reasons of race.

“I was afraid that some might see it the wrong way. They might not understand that we chose Davis because he personified Duty, Honor, Country,” he said, adding that any candidate for a barracks name commemoration at West Point also had to be a general. “We were worried a little bit that there was going to be some blowback, and what I was most heartened by was that there was none. So many people told me how proud they were of West Point, of the Army, and of the nation to have recognized someone as important to all of us as Benjamin O. Davis Jr.”

Granite Versus Action

Yet, no matter how impressive the monument, building, or ceremony, it might all ring hollow if there weren’t active policies in place to back up the gesture, showing how the Academy has evolved since Davis’s days as a cadet.

“The thing you have to continue to ask is, ‘What can we do to make it better?,’” said Bulls. Bulls recalled how he participated in Project Outreach when he was a recent graduate in the late seventies. For a year he worked in the USMA Admissions Office, where he and other grads went into underserved communities and visited junior high school students to expose them to West Point and the military.

“I’ve got to tell you there were ups and downs for African American cadet enrollment. We went from 50 to 100, but this year we’re well over 200, and that didn’t happen overnight,” he said.

Today, there is a Diversity & Inclusion Endowment which helps fund multiple Leadership, Ethics, and Diversity in STEM workshops each year aimed at middle and high school aged youth in underserved areas and cities.

African Americans now make up 15 percent of the Class of 2021. Director of Admissions Colonel Deborah McDonald ’85 credits the growth to WPAOG outreach efforts initiated in the early 1990s. The push led to the formation of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee that encourages graduates of color to keep in touch with their alma mater.

“Once people understand the impact that they have as role models for all cadets, black, white, or whatever, they start to come back,” said Lieutenant General Larry R. Jordan ’68 (Retired), Chairmanof the WPAOG Board, who taught on the USMA History faculty in the mid-1970s. “For cadets, they think, ‘Here’s someone who is a success and enjoying what they do.’ That can’t help but shape their perceptions and their understanding of people from different backgrounds.”

Jordan said that not only do the cadets benefit, but so do the alumni, who gain a better appreciation of what they gained at the Academy.

Those early efforts at building diversity and inclusion at West Point have blossomed into an array of programming (see pp. 12- 13), ranging from the Diversity Leadership Conference to the EXCEL Scholars Program and the West Point Center for Leadership and Diversity in STEM. The programming has grown to encourage understanding beyond the African American community at West Point. There are more than 15 cadet cultural clubs, including: the Asian-Pacific Forum, the Gospel Choir, the Society of Women Engineers, the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers, the Corbin Forum, the Native American Heritage Forum, and National Society of Black Engineers.

Living History

Back in 1977, merely celebrating Black History week (it was only a week back then) was a significant advance for the Academy, said Bulls. That year also happened to be the centennial of the graduation of Henry O. Flipper, allowing Jordan and his history colleagues to celebrate a century of black history at the Academy. Up to that point, a bust of Flipper in the library was the only significant monument to a black graduate, making it a touchstone for many black cadets, quite literally for some.

“Every day I would pass Flipper’s bust in the library, and I would touch it every time I went by; it is what kept me going,” said Priscilla “Pat” Locke ’80, West Point’s first black female graduate, who continues to work to recruit diverse applicants for West Point. “We didn’t have any African American monuments back then, and there wasn’t a lot of visibility of what African Americans have done at the Academy, and so I just didn’t have a good sense of what I was getting myself into.”

Locke said that the Davis Barracks is much more significant than a bust, particularly when the nation is in the midst of a national conversation about monuments. It’s a conversation that, not surprisingly, has been going on for years at West Point as well.

Brigadier General Andre H. Sayles ’73 (Retired), Ph.D., who served eight years as Professor and Head of the USMA Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, was well aware of the Flipper bust and the need for more tributes to African Americans at West Point. He and his colleagues had successfully lobbied to have South Auditorium renamed in 2000 for General Roscoe Robinson ’51, the first African American 4-star Army general, and the first to command the 82nd Airborne Division. “We successfully argued that, even though there was no precedent, the purpose for that name was for cadets to see the name above the stage and ask ‘Who is this guy?’” he said. “We realized that a lot of cadets don’t believe that they can do something unless someone who looks like them has done it,” said Sayles.

But in addition to bronze, bricks and mortar, today there’s coursework and research that allows cadets to engage with the Academy’s past. After the Davis Barracks dedication, a symposium was held examining the life of General Davis. And while the speakers were exhaustive in their accounts of Davis and the Tuskegee Airmen, there remains much research to be done, said Seidule.

“Here at West Point, we need to take the 20th century and just look at the African American experience,” he said. “Quite a bit has been written about African Americans at West Point in the 19th century, but we only had a handful of African Americans in every class up until 1973, and I think that is a great period that’s open for research.”

Daniel Haulman, Ph.D., Chief of the Organizational History Division at the Air Force Research Agency, and a panelist at the symposium, said that history students might look beyond what the Tuskegee Airmen did during World War II, and examine what they did after the war, or what they did in Korea, in Vietnam, or in civilian life.

“Many of them became activists in the Civil Rights Movement and many of them became very important political leaders and educational leaders,” he said. “I don’t think there’s been a lot of research on that.”

The Davis Legacy

As the new Davis Barracks has shown, studying history can change history. It certainly influenced one of Seidule’s students. Michael Barlow would occasionally pop in to his professor’s office to talk sociology, history, and justice. He held strong opinions that he didn’t hide. But as a student of history, he said he recognized that conditions at the Academy had changed dramatically, allowing him to give voice to his ideas, due in no small part to Davis’s efforts.

“I’m opinionated and I study the things I want to study because of the sacrifices Davis made,” said Barlow.

It could be argued that Davis’s “silenced” voice has found a voice in a new generation. But General Gorden said that portraying Davis as an activist would be a misleading.

“He was almost the inverse of an activist. I cannot get the word ‘activism’ to fit him,” he said. “But I can very certainly say that, by his example, anyone who wanted to know what it meant to live, breathe, eat, and sleep the values and ideals of being American, they would find that in him—and, by the way, wasn’t he a great military leader!”

Gorden added that he believed that Davis “would be greatly surprised” to see his legacy in stone, and he added that the young cadets who worked to see him nominated represent an evolution at the Academy that led to a desire “to see things that reflect greater diversity.”

For his part, Barlow said that he was “just an organizer,” and rattled off the names of several cadets who also went door-to-door for signatures from fellow black cadets in support of naming the barracks for Davis.

“There were fights between us, we had disagreements, there were some late nights, stress, and I was ridiculed, but I can’t compare what I went through with what Davis endured,” he said. He credits General Caslen for taking the cadets’ suggestion. “All we did was lobby the committee; he deserves credit for making that recommendation and taking it to the higher generals of the Army,” he said.

But Barlow added that he doesn’t expect the naming of Davis Barracks to fix the subtle aspects of racism. That requires exposure and education, he said. But for new black plebes, it will show them that they’re welcome.

What did he learn in the process?

“Don’t be afraid to be bold, be brave, and stand for what is right, even when it gets tough. Because right is right.”

General Davis would have likely agreed.

David Adjay's Elegant Homage

Modern Magazine, Summer 2017

The new National Museum of African American History and Culture designed by architect David Adjaye is set to open on September 24 on the mall in the nation’s capital. For architects and designers, it is, perhaps, the most anticipated design to land on the mall in many years after several recent designs took rather well-worn approaches.

Modern Magazine, Summer 2017

The new National Museum of African American History and Culture designed by architect David Adjaye is set to open on September 24 on the mall in the nation’s capital. For architects and designers, it is, perhaps, the most anticipated design to land on the mall in many years after several recent designs took rather well-worn approaches.

The Adjaye design is unlike anything the city has seen before: a “dark presence in a city of white marble,” as the museum’s Deputy Director Kinshasha Holman Conwill calls it. But dark here is a color, not a mood. The design is anything but brooding.

Like an inverted ziggurat, the bronze colored filigree façade takes its cue from the crown-like capital of a West African Yoruban column, which the architect refers to as a corona. The cladding also borrows from architectural ironwork made by African-American artisans in the South.

The cladding “is variable in density, to control the amount of sunlight reaching the inner wall,” Adjaye wrote in an email. “During the daytime, the outer skin can be opaque at oblique angles, while allowing glimpses through to the interior at certain moments.”

The filigree façade covers what is essentially a glass atrium cube atop a stone-clad base. Openings in the corona frame vistas of the National Mall, symbolizing views of the nation’s capital through an African American “lens.”

“Those 3,600 panels are viewsheds that let you look out onto the mall, so within this African American space you look out at this cartography of the American capital,” Conwill says.

Initially, the façade was to be bronze, but the weight of cantilevering the metal screens off the core proved too heavy—to say nothing of too costly. Instead the panels were made of aluminum with a five-step bronze-colored finish. “Value engineering is just a part of the process,” Adjaye says. “In this case, the choices we made relating to the material for the façade were more about refining an idea and working out how to make it viable—economically, environmentally, and structurally.”

Much of the exhibition space rests underground, influenced in part by the National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York designed by African-American architect J. Max Bond Jr., whose firm Davis Brody Bond collaborated with Adjaye Associates. Both museums deal with weighty issues at a subterranean level before guiding visitors up to a redeeming light-washed atrium.

The corona form “is a ziggurat that moves upward to the sky, rather than downward into the ground. And it hovers above the ground,” Adjaye writes. “When you see this building, the opaque parts look like they are being levitated above a light space, so you get the sense of an upward mobility in the building. And when you look at the way the circulation works, everything lifts you up into the light.”

Outside the museum, landscape architect Kathryn Gustafson of GGN applies a very light touch with trees native to the Southeast, including a reading grove of “brush arbor,” which would’ve been familiar to plantation slaves as a place to gather for prayer, get away from the main property, or plot an escape.

Conwill says that the initial design process began with a poem—Langston Hughes’s “I too,” in which he writes, “I, too, sing America, I am the darker brother.” “It really started in those regions of poetic imagination, even before there was a design team,” Conwill says. “Poetry has led the way to concepts of history.”

Adjaye says he drew inspiration from the music of his brother, composer Peter Adjaye, as well as from his playlist. He also cited Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s essay on Japanese aesthetics, In Praise of Shadows, as the first among many books he read while working on the project.

The selection of Adjaye, who was born in Africa and is based in London, conjures questions as to why an African American wasn’t chosen, though the African American– led Devrouax & Purnell, who submitted a proposal with Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, was a finalist. “As the design process started it became fitting that, as the story starts in Africa, having an African architect made a lot of sense,” Conwill says. “In the end it didn’t seem strange that those who work in the diaspora could work here, and ultimately it became an African and African Americans designing this museum.”

As a Smithsonian Institution, the museum wasn’t required to hire a certain percentage of minorities, but Conwill says the museum took pains to bring diversity to the construction team and set goals of hiring 15 to 20 percent minority- and women-owned businesses. She added that that exhibition designer Ralph Appelbaum brought in a primarily African American team. And Derek Ross, who is African American, managed construction.

Yet, the completed museum and the resulting media attention will no doubt place Adjaye front and center as a media spokesperson for the African American experience.

“For me, the story is one that’s extremely uplifting, as a kind of world story,” he says. “It’s not a story of a people that was taken down, but actually a people that overcame and transformed an entire superpower into what it is today.”

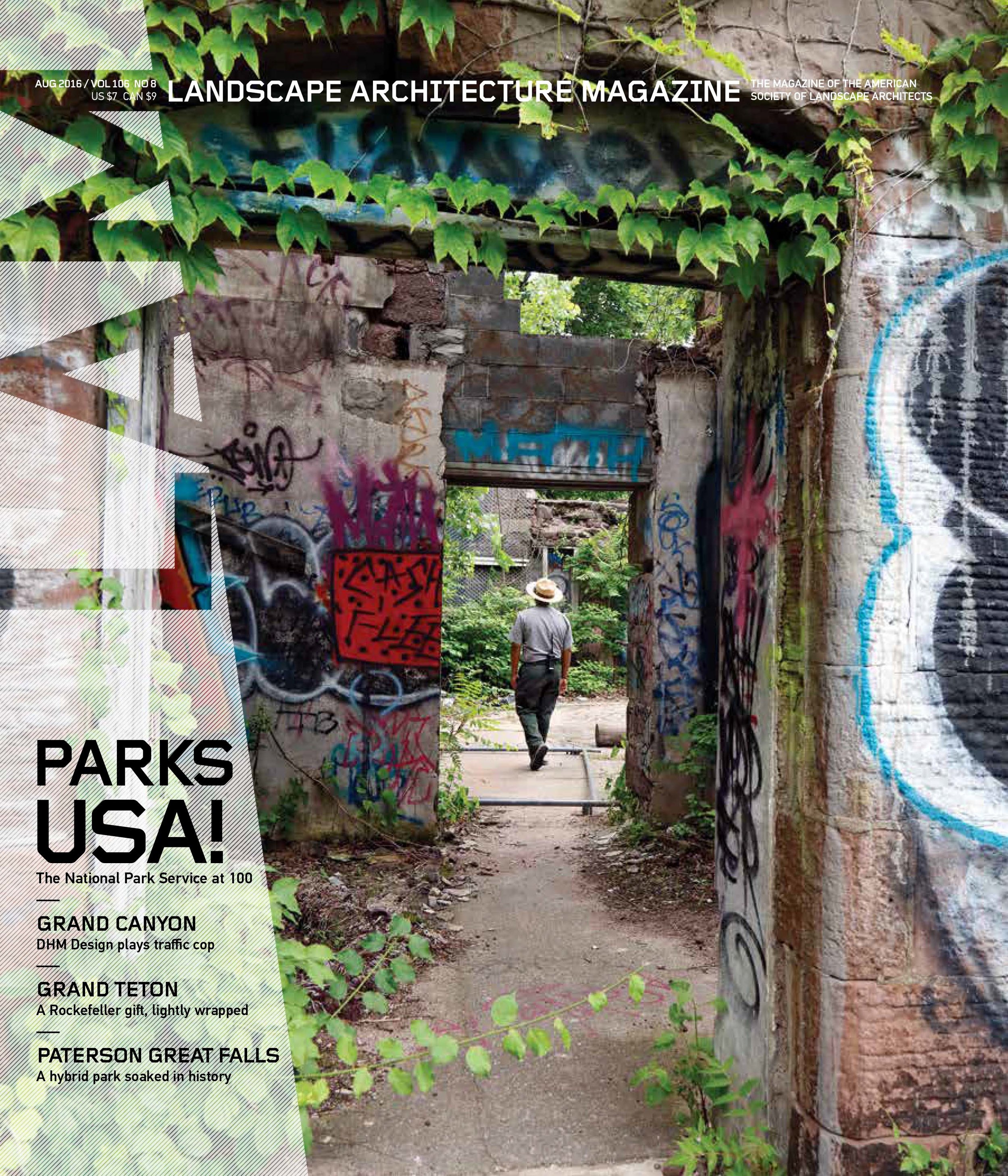

Paterson Falls Rising

Cover Story: Landscape Architecture Magazine, August 2016

Paterson, New Jersey, is a tough town. Gang violence is prevalent, teachers are being laid off, and nearly 30 percent of the city’s residents live in poverty. But the city’s got soul. On Market Street, the lively main thoroughfare, bachata music spills from 99-cent stores, and the scent of Peruvian food wafts through the air. Paterson has been a magnet for immigration since the 19th century, and the reason why is found nearby. Twenty minutes from the center of town is the Great Falls, now part of Paterson Great Falls National Historic Park, where the Passaic River makes a majestic drop of 77 feet off basalt rock cliffs before it continues its twisted path. These are the falls that made Paterson.

Paterson, New Jersey, is a tough town. Gang violence is prevalent, teachers are being laid off, and nearly 30 percent of the city’s residents live in poverty. But the city’s got soul. On Market Street, the lively main thoroughfare, bachata music spills from 99-cent stores, and the scent of Peruvian food wafts through the air. Paterson has been a magnet for immigration since the 19th century, and the reason why is found nearby. Twenty minutes from the center of town is the Great Falls, now part of Paterson Great Falls National Historic Park, where the Passaic River makes a majestic drop of 77 feet off basalt rock cliffs before it continues its twisted path. These are the falls that made Paterson.

In 1778, Alexander Hamilton, General George Washington’s aide-de-camp, recognized the river’s potential to harness power for both manufacturing and geopolitics. Hamilton understood the young nation needed to grow its industry to be independent of Europe. Through a group he helped form in 1791, the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures, Hamilton chose Paterson as the site of the nation’s first planned manufacturing development.

Gianfranco Archimede, who today directs Paterson’s Historic Preservation Commission, said: “At the end of the war, the king essentially said, ‘We’re done with this. Let’s pack up our things and go home. Good luck, you guys. His thought was, we couldn’t get far, because we really couldn’t make any money.”

The Society drafted Pierre Charles L’Enfant to design the site. This was not the aesthete L’Enfant we know from Washington, D.C.; this was a utilitarian L’Enfant, who sought to squeeze profits from a natural wonder. The plan included a waterway system that evolved into the raceways seen in the park today. The diverted water powered several different types of industrial and mill structures along the east side of the river—making silk, cotton, flour, buttons, paper. L’Enfant also suggested the layout of the nearby town. The manufacturing blossomed and remains part of the city’s identity.

The city has maintained a dense population of 145,000, but it hit its height during the Industrial Revolution, continued strong through the Depression, and then started to shrink after World War II. In 1910, Paterson, once known as “Silk City” for its robust textile industry, had 300 factories that employed 18,000 people. After World War II, 34,000 people held manufacturing jobs in Paterson. But by the late 1960s the city had lost 40 percent of those jobs, and another 50 percent were gone by the 1970s because employment had moved to the South and overseas, where labor and operating costs were cheaper. Manufacturing dwindled. Many mills and factories closed. Gone were the Rogers Locomotive factory, the Ivanhoe paper mill, and Allied Textile Printing.

That legacy left behind about 150 industrial buildings of which 30 percent still stand in some form today in the park and the national historic district that surrounds it. These resources, along with the natural beauty of the falls, prompted city and state officials to lobby for the park’s preservation.

In 1972, the site became a National Natural Landmark, and in 2011, it became a National Historic Park. This past June, after several years of consulting with community stakeholders, the National Park Service, adopted a 20-year General Management Plan that merges the park’s two great assets: its history and its natural landscape.

Darren Boch, the park’s superintendent, admitted that initially the park service was not eager to add the Paterson Great Falls to its roster. It already had manufacturing history covered in Lowell, Massachusetts, at the well-regarded Lowell National Historical Park. But Paterson was arguably more knit into the country’s history than Lowell.

Boch was born in Paterson. He uses the pronoun “we” when referring to Paterson, with the kind of authority only a local could assume. His uncle was a batboy at Hincliffe Stadium, the former Negro League ballpark that was recently incorporated into the park. His grandparents made men’s suits at a factory in town. His family moved to nearby Fair Lawn in the 1950s. He remembers the city’s decline. As factories closed, they left brownfields behind. History and natural beauty aside, Boch said restoring Paterson Great Falls is a massive undertaking.

“There was probably some concern about the sustainability of a park here. Not the socioeconomic problems associated—that exists in a lot of urban park areas. But with the current condition, it just seemed like a herculean task. And it is,” Boch said.

Part of the park’s charm is how deeply intertwined the natural and industrial landscapes are. One of the best views of the park’s most dramatic natural assets, the falls, are from the park’s center at Overlook Park. Even here, industry nudges in: bridges crisscross the view, and a hydroelectric plant that powers 10,000 homes sits in the foreground.

“It’s fascinatingly utilitarian, and there’s a real beauty in that. The functional landscape can be just beautiful,” says Karen Tamir, ASLA, a senior associate at James Corner Field Operations and the project manager for the park’s master plan. “I think we romanticize the past. At the time, I doubt anyone thought it was beautiful.”

Field Operations was brought to the site after winning a competition in 2006, administered by the New Jersey Council on the Arts, which asked New Jersey Institute of Technology to run the competition. The firm envisioned the site as a series of rooms, which was a way of organizing the site and making sense of a complex puzzle with historical fragments that span more than two centuries. There is an archeology room, a river room, a forest room, and, of course, a Great Falls room. The plan brings the park experience down to the human scale, to encourage local use of the park’s 52 acres, while also defining the assets to appeal to a regional and national audience. The master plan’s approach has served as a guide for the park service’s General Management Plan, which was just approved in June.

Some of the park’s advocates would like to see the Field Operations plan adopted more fully. Leonard A. Zax, the president of the park’s nonprofit partner, Hamilton Partnership for Paterson, says that the Field Operations plan is “nuanced and masterful.” He says that the essence of any master plan is that there will be modifications along the way because budget and circumstances change.

“Another piece to this is politics and that human beings implement plans—and as shocking as it may seem, we have politics here in New Jersey,” he says wryly. “We don’t to do this in a studio in Chelsea; we do this in the real world.”

Today, the park feels like a work in progress. There are areas that are newly restored and where the plantings have yet to mature; in other sections, the overgrowth and deterioration seem to have progressed for decades. But the spectacular falls keep people coming—especially after a good rain, when the region’s residents know the falls are at their strongest.

The park is open to the city, and people can enter from many directions, but it seems logical for a tourist to start at the park’s center at Overlook Park, which is near the visitor center. It’s also where you can view the falls straight on and assess the lay of the land. Pamphlets provided by the park’s nonprofit suggest visitors walk west across the Great Falls Bridge and then retrace their steps east to the tiered landscape of the raceways, which are skirted by several red-brick factories built in the 19th century.

The raceway system still defines the park on the east side of the river. Visitors who walk from the upper to the middle raceway can see former wheelhouses of the mills. However, the water was diverted from the raceways in 2010. The wheels of the wheelhouses that once captured the water have been removed. Landscape ghosts abound. Brickwork on the façade of the Ivanhoe Wheelhouse infers where a wheel once turned, and grasses grow where water once flowed.

Back at Overlook Park, reached via the middle raceway, visitors cross the Great Falls Bridge or take in the entire vista from the Great Falls Lawn View, where the park service plans to include an amphitheater for which the falls will serve as a backdrop. The park service is also creating a $4.3 million great lawn next to the mill ruins, and $750,000 will go toward clearing overgrowth near Overlook Park, providing views to passing cars and new access points for pedestrians. Both the great lawn and the amphitheater were in the Field Operations plan. And just last month Leonard Zax, the head of the park’s nonprofit partner, proposed a $19.7 million visitors center at overlook park designed by Ralph Applebaum Associates.

Across the bridge on the north side of the river is Mary Ellen Kramer Park. The recently completed park is somewhat utilitarian. Plantings are few. The lawns are patchy. The furniture consists of standard-issue benches and picnic tables. But the park features a restored stone wall with a low rail that brings visitors tantalizingly close to the falls.

The park is named is named for the wife of former Mayor Pat Kramer who fought to prevent a highway from plowing through the site in the late 1960s. Today, the diverted highways created a spaghetti pattern of highways near Paterson’s downtown that contort to avoid running into the park. In June, the county completed a circulation study to cut traffic congestion in and around the park, which is a result of overflow from the diverted highways.

The NPS discourages its parks from accepting brownfields. As a result the ownership of the Paterson Falls is a bit of a partchwork. It’s more cost effective for the city to do the remediation then turn the land over to the park system section by section, as was the case with Mary Ellen Kramer Park. This will continue to be the case as sections are completed by the city with funds coming primarily from the city, state, county, and the Hamilton Partnership.

Next to Mary Ellen Kramer Park is another park asset, the 10,000-seat Hincliffe Stadium. It is said to be the only stadium in the national park system and one of the few sites to explore sports history. The field, which was incorporated into the park in 2014, is a storied home of Hall of Famer Larry Doby, who broke the American League color barrier in 1947. People from all over Paterson came to the games, Boch said. “The players were segregated, but the fans weren’t,” he said. “In the stands, they desegregated themselves.”

When Theodore “T.J.” Best was in high school, his freshman class was one of the last to play on the field before it close in 1997. The field is still owned by the city’s school district. Today he is the director of the Board of Chosen Freeholders, the county’s governing body. The school district can’t afford to run the field, let alone raise the $25 million to $35 million it might take to restore it.

“Despite its historic and architectural significance, the price tag associated with it is pretty steep,” Best said. “Considering the city's and the school district’s many needs, without any real private investment, we might lose it.”

A short distance from the stadium is the Valley of the Rocks, a path that drops about 90 feet below to the falls, and an area informally known as “The Beach.” Today, boys pitch rocks into the water, yell, and curse as they have for years.

“That was me,” Best said.

The path through the Valley of the Rocks is home to a hardwood forest of white oak, sycamore, Norway maple, and white ash. But according to the Field Operations plan, invasive species and weak understory have left the area with “no rare or valuable species growing on the site.”

Across the river, next to Overlook Park, are the mill ruins of the lower raceway. The area is fenced off from the public, not that the fence stops anyone from going there, as the elaborate graffiti murals attest. With each passing day, the mill ruins continue to crumble. Thieves steal the brownstones of the Colt Gun Mill, as well as the chain link fence that guards them. Comparatively, the graffiti seems a tame affront.

Best said he remembers the excitement of discovering this forbidden zone. He made a distinction between the two graffiti styles, labeling one “domestic,” or local, and the other “imported.” Best says that the imported version is probably the work of artists drawn to the area by the Paterson Art Factory, a recently shuttered artist cooperative that closed over safety violations and unpaid taxes. Boch says that although he would never consider graffiti acceptable on the park’s historic landmarks, he didn’t rule out leaving room for graffiti mural in certain areas of park, as they represent yet another layer of the area’s cultural and artistic heritage.

“We don’t look at it positively, but, to be frank, there's some graffiti that’s quite beautiful and can be considered a part of the cultural landscape in some ways,” he said. “The Great Falls has been a haven for various forms of art. Performing and visual artists of all sorts have always been inspired here. These graffiti artist could just be modern versions of those being inspired in different ways and different forms.”