Paterson Falls Rising

Paterson, New Jersey, is a tough town. Gang violence is prevalent, teachers are being laid off, and nearly 30 percent of the city’s residents live in poverty. But the city’s got soul. On Market Street, the lively main thoroughfare, bachata music spills from 99-cent stores, and the scent of Peruvian food wafts through the air. Paterson has been a magnet for immigration since the 19th century, and the reason why is found nearby. Twenty minutes from the center of town is the Great Falls, now part of Paterson Great Falls National Historic Park, where the Passaic River makes a majestic drop of 77 feet off basalt rock cliffs before it continues its twisted path. These are the falls that made Paterson.

In 1778, Alexander Hamilton, General George Washington’s aide-de-camp, recognized the river’s potential to harness power for both manufacturing and geopolitics. Hamilton understood the young nation needed to grow its industry to be independent of Europe. Through a group he helped form in 1791, the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures, Hamilton chose Paterson as the site of the nation’s first planned manufacturing development.

Gianfranco Archimede, who today directs Paterson’s Historic Preservation Commission, said: “At the end of the war, the king essentially said, ‘We’re done with this. Let’s pack up our things and go home. Good luck, you guys. His thought was, we couldn’t get far, because we really couldn’t make any money.”

The Society drafted Pierre Charles L’Enfant to design the site. This was not the aesthete L’Enfant we know from Washington, D.C.; this was a utilitarian L’Enfant, who sought to squeeze profits from a natural wonder. The plan included a waterway system that evolved into the raceways seen in the park today. The diverted water powered several different types of industrial and mill structures along the east side of the river—making silk, cotton, flour, buttons, paper. L’Enfant also suggested the layout of the nearby town. The manufacturing blossomed and remains part of the city’s identity.

The city has maintained a dense population of 145,000, but it hit its height during the Industrial Revolution, continued strong through the Depression, and then started to shrink after World War II. In 1910, Paterson, once known as “Silk City” for its robust textile industry, had 300 factories that employed 18,000 people. After World War II, 34,000 people held manufacturing jobs in Paterson. But by the late 1960s the city had lost 40 percent of those jobs, and another 50 percent were gone by the 1970s because employment had moved to the South and overseas, where labor and operating costs were cheaper. Manufacturing dwindled. Many mills and factories closed. Gone were the Rogers Locomotive factory, the Ivanhoe paper mill, and Allied Textile Printing.

That legacy left behind about 150 industrial buildings of which 30 percent still stand in some form today in the park and the national historic district that surrounds it. These resources, along with the natural beauty of the falls, prompted city and state officials to lobby for the park’s preservation.

In 1972, the site became a National Natural Landmark, and in 2011, it became a National Historic Park. This past June, after several years of consulting with community stakeholders, the National Park Service, adopted a 20-year General Management Plan that merges the park’s two great assets: its history and its natural landscape.

Darren Boch, the park’s superintendent, admitted that initially the park service was not eager to add the Paterson Great Falls to its roster. It already had manufacturing history covered in Lowell, Massachusetts, at the well-regarded Lowell National Historical Park. But Paterson was arguably more knit into the country’s history than Lowell.

Boch was born in Paterson. He uses the pronoun “we” when referring to Paterson, with the kind of authority only a local could assume. His uncle was a batboy at Hincliffe Stadium, the former Negro League ballpark that was recently incorporated into the park. His grandparents made men’s suits at a factory in town. His family moved to nearby Fair Lawn in the 1950s. He remembers the city’s decline. As factories closed, they left brownfields behind. History and natural beauty aside, Boch said restoring Paterson Great Falls is a massive undertaking.

“There was probably some concern about the sustainability of a park here. Not the socioeconomic problems associated—that exists in a lot of urban park areas. But with the current condition, it just seemed like a herculean task. And it is,” Boch said.

Part of the park’s charm is how deeply intertwined the natural and industrial landscapes are. One of the best views of the park’s most dramatic natural assets, the falls, are from the park’s center at Overlook Park. Even here, industry nudges in: bridges crisscross the view, and a hydroelectric plant that powers 10,000 homes sits in the foreground.

“It’s fascinatingly utilitarian, and there’s a real beauty in that. The functional landscape can be just beautiful,” says Karen Tamir, ASLA, a senior associate at James Corner Field Operations and the project manager for the park’s master plan. “I think we romanticize the past. At the time, I doubt anyone thought it was beautiful.”

Field Operations was brought to the site after winning a competition in 2006, administered by the New Jersey Council on the Arts, which asked New Jersey Institute of Technology to run the competition. The firm envisioned the site as a series of rooms, which was a way of organizing the site and making sense of a complex puzzle with historical fragments that span more than two centuries. There is an archeology room, a river room, a forest room, and, of course, a Great Falls room. The plan brings the park experience down to the human scale, to encourage local use of the park’s 52 acres, while also defining the assets to appeal to a regional and national audience. The master plan’s approach has served as a guide for the park service’s General Management Plan, which was just approved in June.

Some of the park’s advocates would like to see the Field Operations plan adopted more fully. Leonard A. Zax, the president of the park’s nonprofit partner, Hamilton Partnership for Paterson, says that the Field Operations plan is “nuanced and masterful.” He says that the essence of any master plan is that there will be modifications along the way because budget and circumstances change.

“Another piece to this is politics and that human beings implement plans—and as shocking as it may seem, we have politics here in New Jersey,” he says wryly. “We don’t to do this in a studio in Chelsea; we do this in the real world.”

Today, the park feels like a work in progress. There are areas that are newly restored and where the plantings have yet to mature; in other sections, the overgrowth and deterioration seem to have progressed for decades. But the spectacular falls keep people coming—especially after a good rain, when the region’s residents know the falls are at their strongest.

The park is open to the city, and people can enter from many directions, but it seems logical for a tourist to start at the park’s center at Overlook Park, which is near the visitor center. It’s also where you can view the falls straight on and assess the lay of the land. Pamphlets provided by the park’s nonprofit suggest visitors walk west across the Great Falls Bridge and then retrace their steps east to the tiered landscape of the raceways, which are skirted by several red-brick factories built in the 19th century.

The raceway system still defines the park on the east side of the river. Visitors who walk from the upper to the middle raceway can see former wheelhouses of the mills. However, the water was diverted from the raceways in 2010. The wheels of the wheelhouses that once captured the water have been removed. Landscape ghosts abound. Brickwork on the façade of the Ivanhoe Wheelhouse infers where a wheel once turned, and grasses grow where water once flowed.

Back at Overlook Park, reached via the middle raceway, visitors cross the Great Falls Bridge or take in the entire vista from the Great Falls Lawn View, where the park service plans to include an amphitheater for which the falls will serve as a backdrop. The park service is also creating a $4.3 million great lawn next to the mill ruins, and $750,000 will go toward clearing overgrowth near Overlook Park, providing views to passing cars and new access points for pedestrians. Both the great lawn and the amphitheater were in the Field Operations plan. And just last month Leonard Zax, the head of the park’s nonprofit partner, proposed a $19.7 million visitors center at overlook park designed by Ralph Applebaum Associates.

Across the bridge on the north side of the river is Mary Ellen Kramer Park. The recently completed park is somewhat utilitarian. Plantings are few. The lawns are patchy. The furniture consists of standard-issue benches and picnic tables. But the park features a restored stone wall with a low rail that brings visitors tantalizingly close to the falls.

The park is named is named for the wife of former Mayor Pat Kramer who fought to prevent a highway from plowing through the site in the late 1960s. Today, the diverted highways created a spaghetti pattern of highways near Paterson’s downtown that contort to avoid running into the park. In June, the county completed a circulation study to cut traffic congestion in and around the park, which is a result of overflow from the diverted highways.

The NPS discourages its parks from accepting brownfields. As a result the ownership of the Paterson Falls is a bit of a partchwork. It’s more cost effective for the city to do the remediation then turn the land over to the park system section by section, as was the case with Mary Ellen Kramer Park. This will continue to be the case as sections are completed by the city with funds coming primarily from the city, state, county, and the Hamilton Partnership.

Next to Mary Ellen Kramer Park is another park asset, the 10,000-seat Hincliffe Stadium. It is said to be the only stadium in the national park system and one of the few sites to explore sports history. The field, which was incorporated into the park in 2014, is a storied home of Hall of Famer Larry Doby, who broke the American League color barrier in 1947. People from all over Paterson came to the games, Boch said. “The players were segregated, but the fans weren’t,” he said. “In the stands, they desegregated themselves.”

When Theodore “T.J.” Best was in high school, his freshman class was one of the last to play on the field before it close in 1997. The field is still owned by the city’s school district. Today he is the director of the Board of Chosen Freeholders, the county’s governing body. The school district can’t afford to run the field, let alone raise the $25 million to $35 million it might take to restore it.

“Despite its historic and architectural significance, the price tag associated with it is pretty steep,” Best said. “Considering the city's and the school district’s many needs, without any real private investment, we might lose it.”

A short distance from the stadium is the Valley of the Rocks, a path that drops about 90 feet below to the falls, and an area informally known as “The Beach.” Today, boys pitch rocks into the water, yell, and curse as they have for years.

“That was me,” Best said.

The path through the Valley of the Rocks is home to a hardwood forest of white oak, sycamore, Norway maple, and white ash. But according to the Field Operations plan, invasive species and weak understory have left the area with “no rare or valuable species growing on the site.”

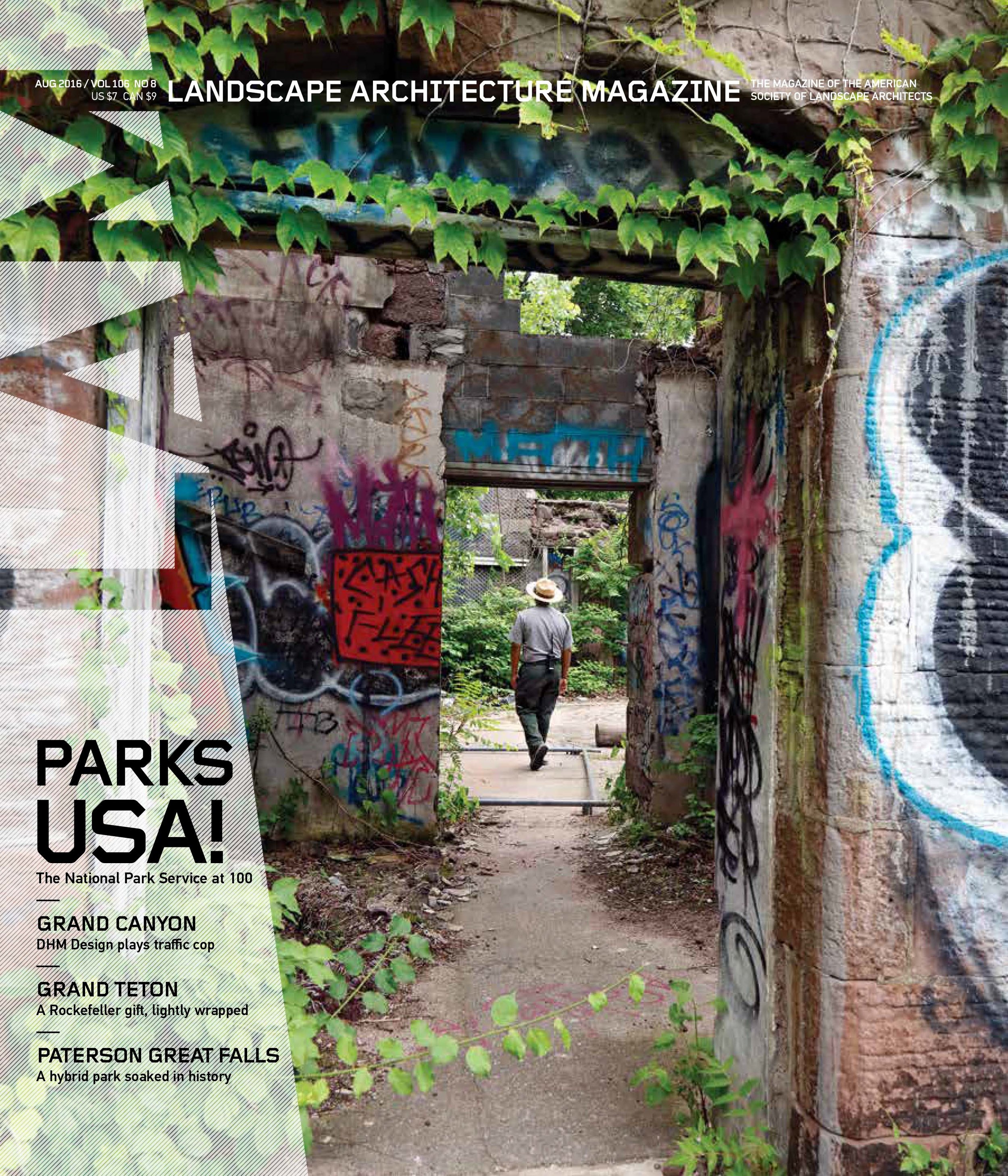

Across the river, next to Overlook Park, are the mill ruins of the lower raceway. The area is fenced off from the public, not that the fence stops anyone from going there, as the elaborate graffiti murals attest. With each passing day, the mill ruins continue to crumble. Thieves steal the brownstones of the Colt Gun Mill, as well as the chain link fence that guards them. Comparatively, the graffiti seems a tame affront.

Best said he remembers the excitement of discovering this forbidden zone. He made a distinction between the two graffiti styles, labeling one “domestic,” or local, and the other “imported.” Best says that the imported version is probably the work of artists drawn to the area by the Paterson Art Factory, a recently shuttered artist cooperative that closed over safety violations and unpaid taxes. Boch says that although he would never consider graffiti acceptable on the park’s historic landmarks, he didn’t rule out leaving room for graffiti mural in certain areas of park, as they represent yet another layer of the area’s cultural and artistic heritage.

“We don’t look at it positively, but, to be frank, there's some graffiti that’s quite beautiful and can be considered a part of the cultural landscape in some ways,” he said. “The Great Falls has been a haven for various forms of art. Performing and visual artists of all sorts have always been inspired here. These graffiti artist could just be modern versions of those being inspired in different ways and different forms.”

Paterson and its Great Falls continue to inspire artists and poets, as they inspired William Carlos Williams’s five books of poetry titled Paterson and the photographer George Tice’s monographs of Paterson photographs from 1972 and 2006, titled Paterson and Patterson II. And this fall, director Jim Jarmusch will release Paterson, starring Adam Driver as a character named Paterson.

The movie should make new audiences aware of the park and the city, and making people aware of Paterson seems to be at the top of everyone’s priorities.

Low rents and the proximity to New York City, about 45 minutes away, continue draw immigrants to city. “Even though Paterson is economically depressed and is no longer a manufacturing center, the city still has this lure of first-generation Americans coming here and raising families to get their slice the American dream,” says Vincent Parrillo, a professor at William Paterson University and the director of the Paterson Metropolitan Region Research Center. “Everything is relative—being poor in Paterson is not like being poor in Mexico or Bangladesh.”

Last year, the National Parks NOW competition, organized by the Van Alen Institute and the NPS, selected Paterson as one of its challenge sites. A group called Team Paterson won with “Great Falls, Great Stories, Great Food,” a plan to map the city’s foodways and drive visitors to the city’s restaurants, which are rich in Peruvian cuisine, but also in Colombian, Dominican, Jamaican, Syrian, Turkish, and Lebanese.

“We need to enlarge the audience for national parks because they are for everyone and could invite new audiences who have been less inclined to take advantage of these resources,” said Team Paterson’s leader, June Williamson, an associate professor of architecture at CUNY’s Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture.

Zax expects that people will increasingly come to appreciate that Peruvian food is not only excellent but is available within a 10-minute walk from the falls. “Our mantra,” he said, “will always be that the park is the city and the city is the park.”